By Mike Stonelake

initially published in the Sourozh Magazine No. 107 year 2011, pp. 14-21

Cuthbert was an Anglo-Saxon, born in the 7th century, to lowly parents. As a young man he was a shepherd and a soldier, like Moses and David before him. These disciplines served as preparation for Cuthbert and his subsequent life as a monk, teaching him endurance of physical hardship, abstention, solitude and obedience. When referring to Saint Cuthbert in Russia he is most often compared to Saint Seraphim of Sarov for his kindness and dedication to the Saviour.

There has never been a saint in Britain as well loved as Saint Cuthbert. Even during his life and ministry as a monk, evangelist and bishop, he was loved by his fellow monks, royalty and common folk. Immediately after his death his grave became a magnet for pilgrims, with miracles in abundance. After Henry VIII’s iconoclastic reformation and dissolution of the monasteries, Cuthbert’s body was one of the few that were left undisturbed and, at the start of the 1st century, the saint continues to inspire Catholics, Anglicans, Orthodox and non-conformists alike.

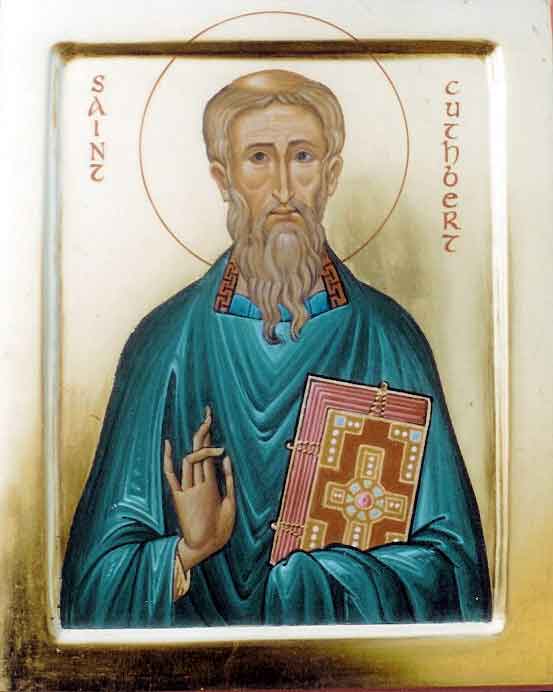

Saint Cuthbert of Lindisfarne (source of the icon)

Cuthbert was born in 635, at a time when Britain was at a crossroads. The ancient Celtic expression of Christianity was still strong in Cornwall, Wales, Ireland and Scotland, and was centred around the monasteries, which looked to the desert fathers for inspiration and appropriated traditions from the pagan, Celtic culture that preceded it. The wonderful jewellery, carvings and metalwork, with their intertwined abstract animal forms, were absorbed by Christianity and re-emerged as decoration for religious books and stone crosses. In the same way, Celtic literature,

such as the heroic Táin Bó Cúailnge (TheCattle Raid of Cooley), resurfaced in tales about the saints, such as the fantastical Voyage of Saint Brendan. This romantic, fiercely independent faith was directly challenged by the might of the Roman Church, with its hierarchy, institutions and resources. Many saw Roman Christianity as the way back into a world they had been isolated from for several hundred years, and ultimately, Rome prevailed.

Cuthbert was an Anglo-Saxon, born in the 7th century, to lowly parents. As a young man he was a shepherd and a soldier, like Moses and David before him. These disciplines – that had equipped the biblical prophet and king respectively – also served as preparation for Cuthbert, and his subsequent life as a monk, teaching him endurance of physical hardship, abstention, solitude and obedience.

It was while working as a shepherd that Cuthbert saw a vision: ‘…he saw a long stream of light break through the darkness of the night, and in the midst of it a company of the heavenly host descended to the earth, and having received among them a spirit of surpassing brightness, returned without delay to their heavenly home’. In the morning he discovered that Bishop Aidan of Lindisfarne had just died, and at that moment Cuthbert decided to become a monk. We can also speculate that Cuthbert acquired his renowned love of animals whilst tending sheep near Melrose Abbey, where it is also likely that he met and spoke with the monks that lived there.

If we know little of his life as a shepherd, we know even less of his life as a soldier. There is no record of whether he engaged in combat or not during the 4 years he spent in the army, although there was a conflict at this time between the kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia. It is difficult to imagine Cuthbert – who spent his life ministering to the needs of others – ever picking up a weapon to do violence.

However, it is interesting to ponder what memories he might have drawn upon when, many years later, as a monk on Farne Island, facing the evil spirits that lived there, “armed with the helmet of salvation, the shield of faith, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God, all the fiery darts of the wicked were extinguished, and that wicked enemy, with all his followers, were put to flight” (Saint Bede The Venerable, The Life of Saint Cuthbert).

On leaving the army, Cuthbert travelled to Melrose Monastery, near the Scottish border, where he was accepted as a monk, and was made Guest-Master. Despite his dedication to the spiritual life of abstinence and prayer, Cuthbert seemed to understand that the most perfect expression of his love of God was to love and help others, and so he poured his religious zeal into his work as Guest-Master. When travellers arrived in the snow, he would hold their frozen feet to his breast to warm them.

It is from this time that the famous story of Saint Cuthbert and the otters originates. While on a visit to a religious house in Coldingham, Cuthbert slipped away in the night and walked to the coast, where he submerged himself in the sea up to his neck, spending the night in prayer and worship. The North Sea at Northumbria is not only very cold, but is also rough, with large waves pounding the shore and strong winds blowing. It must have been a daunting experience for Cuthbert, in the freezing cold water, with only the light of the moon, the crash of the waves and howl of the wind. We often think of prayer and contemplation as being silent and peaceful, but Cuthbert had no difficulty in sensing God’s presence in the elements that threatened to engulf him. Indeed, here we see an example of how Cuthbert’s Celtic understanding of spirituality would draw inspiration from nature. And Cuthbert’s oneness with Creation is delightfully demonstrated in what happened next: as he emerged from the sea, two sea otters came up to him and dried him with their fur and their warm breath.

When the prior of Melrose died, in 664, Cuthbert was given the post. However, in this same year, the Synod of Whitby ruled in favour of aligning the church with the Roman tradition, and Cuthbert, who obediently accepted the decision of Whitby, was chosen to play a role in easing this transition. So he was moved to the important Monastery of Lindisfarne, on Holy Island, which was founded by Bishop Aidan and followed the Celtic monastic rule. He was an ideal choice, having been raised in the Celtic tradition, but now a follower of Rome. Cuthbert was someone who lived a holy and devout life, who was both sensitive and firm, and who could lead by example. Cuthbert’s rule was largely embraced, although a handful of monks who could not accept the Roman rule returned to Ireland. Lindisfarne Monastery is a remote location, approximately a mile from the coast of Northumbria, and accessible only at low tide. And yet it seems the location was not remote enough for Cuthbert, who yearned for the solitary life, in imitation of the desert fathers that were such an inspiration to him.

Initially, Cuthbert spent much of his time away from the monastery, travelling tirelessly through the countryside, from Berwick to Galloway, evangelising the towns and villages he visited. There were still many pagans at this time, and Cuthbert became renowned among them as a healer and a man of great insight. He won them over

to Christ, and they referred to him as the Wonderworker of Britain.

Eventually, the call to the life of a hermit was so strong in Cuthbert that he left Holy Island. First he made his home on the rocky outcrop that can be reached from Holy Island at low tide – now known as Saint Cuthbert’s Island. However, Cuthbert did not remain here – perhaps not feeling sufficiently isolated – and so he moved to Farne Island, several miles from Lindisfarne, and completely inaccessible, even by boat, for long periods.

It seems that the Celtic saints were always attracted to water: Saint Columba settled on Iona, a small island off the coast of Scotland; Saint Brendan is remembered for his voyage to the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Greenland, spending many months at sea and having many adventures. Many Celtic monks would set themselves adrift in their tiny coracles (small boats made from wood and animal skins) and go wherever God and the tides took them, evangelising much of the continent in this way, and some say, even reaching destinations as distant as Nova Scotia. For these monks, the sea was a place of unlimited possibilities, and a gateway to the heavenly realm. The shores were the margins of life, the outer limits of the habitable, symbolising the monastic life, lived with one foot on earth and one in heaven. The sea, like God’s love, was infinitely wide and deep, unfathomable and beyond our comprehension. In this setting, Cuthbert felt at home, far removed from the comforts of earthly security and worldly possessions. On Farne Island he could spend his days looking out to sea, yearning for the time when he would break free from the earthly life and drift into eternity to be with God.

On Farne, Cuthbert built a rough shelter. Though no trace of it exists today, Saint Bede records that it had just one

window, which offered only a view of the sky, and now tales of the birds start to feature more prominently in his life, as he lifts his eyes to the heavens. He lectured the birds that stole his crops, and we are told that they obeyed and left his crops alone. Some repentant crows brought him a piece of lard, which Cuthbert kept to polish the shoes of visitors. Cuthbert also instigated laws to protect the Eider ducks (now also known as Cuthbert’s Ducks), making Farne Island the first wildlife sanctuary in the world. Today, many species of birds inhabit the island, including shags, cormorants, razorbills, guillemots and puffins, alongside a colony of seals, many rabbits (recently introduced), and the whales, that are often sighted nearby.

Cuthbert’s life on Farne lasted for 8 years, until he was begged to return to Lindisfarne and become a bishop. The years he served as a bishop were marked by more evangelism, and a refusal to leave his life of hardship and self-denial.

But soon Cuthbert started to sense that his earthly life was drawing to a close, and he resigned as bishop so that he could return to Farne Island and his life as a hermit. Shortly after returning to the island, he fell ill. By the time the monks found him, Cuthbert could hardly move and was not eating. He looked quite frightening, with long unkempt hair, uncut nails and clothes that had not been changed for a long time.

Cuthbert’s death, in 687, was signaled to Lindisfarne with candles, and the ordinary folk, many of whom had encountered him personally and even been converted by him, came in their droves, to his body and later his tomb, to pay reverence to his incorruptible remains. In subsequent years, pilgrims travelled to Lindisfarne to visit Cuthbert’s tomb, where miracles occurred.

Cuthbert’s remains were one of the few holy relics to survive the wanton destruction of Henry VIII’s reformation. Today they lie in Durham Cathedral, covered with a marble slab, marked simply with the word “Cuthbertus”.

Source: Russian Orthodox Church in Great Britain and Ireland, Diocese of Sourozh