By Nun Cornelia (Rees)

We have all heard from social activists of all stripes that “you can make a difference.” Can one person make a difference? Yes, they say, you can. There is of course the petition to sign, the donation to make, the offer of your personal time. All good things to be sure; but let us look with amazement and holy awe at how a self-effacing, humble man made such a difference, how he changed the course of his country’s history, and saved it from utter destruction.

We have all heard from social activists of all stripes that “you can make a difference.” Can one person make a difference? Yes, they say, you can. There is of course the petition to sign, the donation to make, the offer of your personal time. All good things to be sure; but let us look with amazement and holy awe at how a self-effacing, humble man made such a difference, how he changed the course of his country’s history, and saved it from utter destruction.

St. Sergius was born to an aristocratic family, during a very violent period of Russian history. His father Cyril and mother Maria were very devout Orthodox Christians, and well known in their native town of Rostov. But they were forced to gather their children, including the future St. Sergius, and flee to the town of Radonezh as a result of the raging disunity in Russian society. The Grand Duke of Moscow had taken over the principality of Rostov, and persecution of the Rostov nobility ensued. Many notable families were relieved of their property and cruelly mistreated; the governor was even executed by hanging, upside-down. The pride and rapaciousness of local princes made life precarious for those on the wrong end of every hostile takeover. With each one looking only to obtain his own benefit, life among these relatively new Christians was becoming untenable. Now as people look back, those with eyes to see, can see that when Christians do not live peacefully with each other, God allows an utterly un-Christian invasion to take place that is not soon erased from their memory.

In the case of fourteenth century Russia, this unforgettable lesson came in the form of Mongol Hordes—ferocious conquerors whose cruelty to the defeated shocked even those who were capable of hanging a local governor by his feet.

Meanwhile, however, St. Sergius is still the boy Bartholomew, the other-worldly son of two very pious parents. Strangers to strife, they settled near the Church of the Nativity of Christ near the village of Radonezh, north of Moscow. Despite the troubles in the land, God’s seed had taken root in Russian soil, and one proof of that was precisely little Bartholomew—the precious fruit of his God-fearing parents. Time would prove the truth of the Gospel parable about the grain of mustard seed—a seemingly insignificant, unknown, humble seed that grows to bring comfort and shelter to all around it.

While others were striving for lands, power, and other people’s wealth, Bartholomew cherished only solitude, prayer, and the good of his neighbor. Having no inclination whatsoever for worldly life and seeking only the life of a monk, Bartholomew nevertheless deferred to his parents, who needed his help until God was pleased to take them to a better life. Obediently postponing his departure for the wilderness, Bartholomew took care of his parents until their repose, then immediately gave his inheritance to his younger brother and began a life of complete simplicity and devotion to God. It was his habit to cut off his own will in everything, deferring always to others. This could be seen in everything he did.

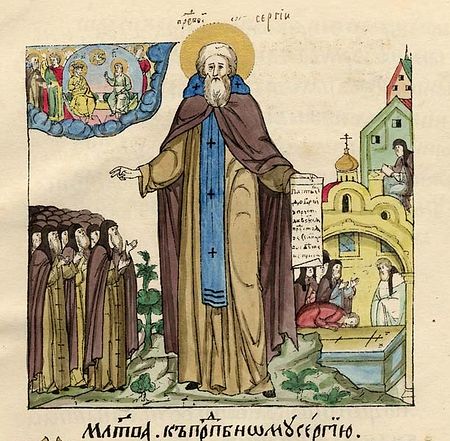

When his older brother joined him in the forest wilderness, they built a small church. Bartholomew asked his older brother, how did he bless the church to be dedicated? Now, there was a family story that made Bartholomew’s deference seem amazing to Stephen. When Bartholomew was a child, he had trouble learning to read and write. After praying hard about this, he was met by a mysterious elder who gave him a prosphora and blessed him to learn. Bartholomew turned from a poor student to a child prodigy overnight. Moreover, the mysterious elder told his parents that the boy would be a servant of the Holy Trinity and save many souls. Then the elder disappeared, leaving them to wonder—had they been visited by an angel on their boy’s account? But humility kept all this in the boy’s heart; and rather than envy him like Joseph’s brothers of old, Stephen reminded him of this sign, saying that without a doubt that the chapel should be dedicated to the Holy Trinity.

This humility would be the hallmark of this very great man. When other brothers, wishing to save their souls, began to gather around him, desiring to live under obedience to him and follow his example, his greatest desire was to serve them in everything. He built cells for them, cooked for them, and considered himself the lowliest of all. When powerful men came to the community seeking his blessing, they were confused by his appearance—he was the worst dressed of the brotherhood, always chopping wood, sawing logs, or doing some equally menial labor. He would take the clothing that no one else wanted and wear it until it became utter rags.

When the brotherhood ran out of food, he did not even dare to insult God’s Providence by asking laypeople to supply them. St. Sergius first went out and asked for work, to earn bread for the brothers. Most of the monks were satisfied with these crusts, but one brother was not happy—the bread was moldy. St. Sergius prayed, and every day for the next few days, fresh loaves were brought to the monastery from an unknown benefactor. St. Sergius showed by his own example how to trust completely in God, and to humble oneself before His will. Certainly if the monks had gone begging bread, they would not have been refused. But they would have been deprived of the sweetness of trusting entirely in God. Because of his faith, St. Sergius was able to teach this principle to them.

St. Sergius’s disciples increased in number, and he continued this soul-saving life. But there was another step he had to take. The brothers begged him to become their abbot; he continually refused, preferring the life of a simple monk. After much pleading he submitted to their request as to God’s will, and became a priest.

The Russian Church in the days of St. Sergius was not a self-ruling Orthodox Church. It was still under the authority of the Patriarch of Constantinople. One day, a group of Greek monks came to visit St. Sergius, having heard of his holy life even as far away as the Byzantine capital. They brought a request from the Patriarch: “Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity! (Ps. 133:1),” was their instruction to him. The Patriarch approved of Sergius’s monastic labors and those of his disciples; however, he felt a monastery was needed. Without any resistance against unwanted “organization”, St. Sergius simply asked, “What should I do?” From that time the monks were assigned their various areas of mutual contribution. If the saint had not agreed to unity, preferring an “individual” expression of sanctity, we would not have the great Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra today, or many other monasteries for that matter, because the saint’s disciples spread this monastic life all over northern Russia. New sprouts have to come from a strong family, and not from a loose affiliation of individuals, however good they may individually be.

The Russian people’s problems with power struggles, treachery, and war between different princes were not over. In the midst of it all, there stood a humble monk, ever avoiding honor or power over others, asking nothing and giving everything. This was a magnetic force that drew together seemingly irreconcilable enemies. Since ancient times, princes of this world have always known and used the tactic of “divide and conquer”, to bring down other nations and gain control over foreign populations. The Mongols used Russia’s in-fighting to their advantage, and turned them into slavish subjects. But St. Sergius, to the contrary, was able through the grace and wisdom given him by God to draw the nation together, and break the bonds. The people would never have been able to cast off the Mongol Yoke if they had not been able to unite. This is a tribute to the saint, but it is also a tribute to the Orthodox Russian nation. Despite their failings and uncontrolled instincts, they were able to understand where their salvation lay, and to finally humble themselves before the sanctity they found in one of their number. When Grand Duke Dimitry of Moscow was confronted with the fierce pagan hordes on the fields of Kulikovo, he could see that he was greatly outnumbered, and he nearly retreated. But just then, a messenger rode up with a message from St. Sergius to go forward and have faith that God will be with him. He obeyed and overcame all doubt. St. Sergius and the monks were praying for them, and they won the battle. Historically, this battle is considered to be the breaking point in the Mongol Yoke.

Having broken that yoke, the nation was free to develop and become strong, and Christian principles were given a chance to prevail. Instead of pyramids of skulls, churches and institutions of charity were built. What is best in man had the chance to unfold and reveal itself, as we can see in Russia’s later development of arts, literature, and statesmanship. When people ceased to struggle for unity and a proper relationship to each other and to God, that unity unraveled, and a new pagan horde came to knock at Russia’s door in 1917.

Truly, what can one man do? Nothing. But with God a man can do anything. St. Sergius proved this, and continues to teach it. What a powerful thing is humility and love of God. What strength there is in unity. Yet how often does it slip away, leaving a manipulable mass of beings, alienated from one another, cohesive with nothing, vulnerable to every pernicious attack. A community, a society that is working toward cohesion and mutual aid is like a hospital where everyone is healing each other.Confess your faults one to another, and pray one for another, that ye may be healed. The effectual fervent prayer of a righteous man availeth much (Js. 5:16). By the prayers of St. Sergius, and by his example of conquering by love, of leading by humility, of submitting all human desires to God, even the most hopeless situations can be turned around for the better.

Holy Father Sergius, pray to God for us!

Source: Pravoslavie.ru